- Home

- Philip K. Dick

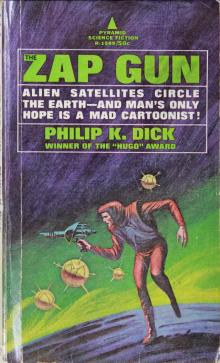

The Zap Gun

The Zap Gun Read online

PHILIP K. DICK

THE ZAP GUN

Philip K. Dick was born in Chicago in 1928 and lived most of his life in California. He briefly attended the University of California, but dropped out before completing any classes. In 1952, he began writing professionally and proceeded to write numerous novels and short-story collections. He won the Hugo Award for the best novel in 1962 for The Man in the High Castle and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for best novel of the year in 1974 for Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said. Philip K. Dick died on March 2, 1982, in Santa Ana, California, of heart failure following a stroke.

NOVELS BY PHILIP K. DICK

Clans of the Alphane Moon

Confessions of a Crap Artist

The Cosmic Puppets

Counter-Clock World

The Crack in Space

Deus Irae (with Roger Zelazny)

The Divine Invasion

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Dr. Bloodmoney

Dr. Futurity

Eye in the Sky

Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said

Galactic Pot-Healer

The Game-Players of Titan

The Man in the High Castle

The Man Who Japed

Martian Time-Slip

A Maze of Death

Now Wait for Last Year

Our Friends from Frolix 8

The Penultimate Truth

Radio Free Albemuth

A Scanner Darkly

The Simulacra

Solar Lottery

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch

Time Out of Joint

The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

Ubik

The Unteleported Man

VALIS

Vulcan’s Hammer

We Can Build You

The World Jones Made

The Zap Gun

The guidance-system of weapons-item 207, which consists of six hundred miniaturized electronic components, can best be plow-shared as a lacquered ceramic owl which appears to the unenlightened only as an ornament; the informed knowing, however, that the owl’s head, when removed, reveals a hollow body in which cigars or pencils can be stored.

Official report of the UN-W Natsec Board of Wes-bloc, October 5, 2003, by Concomody A (true identity for security reasons not to be given out; vide Board rulings XV 4-5-6-7-8).

ONE

“Mr. Lars, sir.”

“I’m afraid I only have a moment to talk to your viewers. Sorry.” He started on, but the autonomic TV interviewer, camera in its hand, blocked his path. The metal smile of the creature glittered confidently.

“You feel a trance coming on, sir?” the autonomic interviewer inquired hopefully, as if perhaps such could take place before one of the multifax alternate lens-systems of its portable camera.

Lars Powderdry sighed. From where he stood on the footers’ runnel he could see his New York office. See, but not reach it. Too many people—the pursaps!—were interested in him, not his work. And the work of course was all that mattered.

He said wearily, “The time factor. Don’t you understand? In the world of weapons fashions—”

“Yes, we hear you’re receiving something really spectacular,” the autonomic interviewer gushed, picking up the thread of discourse without even salutationary attention to Lars’ own meaning. “Four trances in one week. And it’s almost come all the way through! Correct, Mr. Lars, sir?”

The autonomic construct was an idiot. Patiently he tried to make it understand. He did not bother to address himself to the legion of pursaps, mostly ladies, who viewed this early-morning show—Lucky Bagman Greets You, or whatever it was called. Lord knew he didn’t know. He had no time in his workday for such witless diversions as this. “Look,” he said, this time gently, as if the autonomic interviewer were really alive and not merely an arbitrarily endowed sentient concoction of the ingenuity of Wes-bloc technology of 2004 A.D. Ingenuity, he reflected, wasted in this direction … although, on a closer thought, was this so much more an abomination than his own field? A reflection unpleasant to consider.

He repressed it from his mind and said, “In weapons fashions an item must arise at a certain time. Tomorrow, next week or next month is too late.”

“Tell us what it is,” the interviewer said, and hung with bated avidity on the anticipated answer. How could anyone, even Mr. Lars of New York and Paris, disappoint all the millions of viewers throughout Wes-bloc, in a dozen countries? To let them down would be to serve the interests of Peep-East, or so the autonomic interviewer wished to convey. But it was failing.

Lars said, “It’s frankly none of your business.” And stalked past the small bunch of footers who had assembled to gawk, stalked away from the warm glow of instant-exposure before public observation and to the uptrack of Mr. Lars, Incorporated, the single-story structure arranged as if by intention among high-rise offices whose size alone announced the essential nature of their function.

Physical size, Lars reflected as he reached the outer, public lobby of Mr. Lars, Incorporated, was a false criterion. Even the autonomic interviewer wasn’t fooled; it was Lars Powderdry that it wished to expose to its audience, not the industrial entities within easy reach. However much the entities would have delighted in seeing their ak-prop—acquisition-propaganda—experts thundering into the attentive ears of its audience.

The doors of Mr. Lars, Incorporated, shut, tuned as they were to his own cephalic pattern. He sealed off, safe from the gaping multitude whose attention had been jazzed up by professionals. On their own the pursaps would have been reasonable about it; that is, they would be apathetic.

“Mr. Lars.”

“Yes, Miss Bedouin.” He halted. “I know. The drafting department can’t make head or tail of sketch 285.” To that he was resigned. Having seen it himself, after Friday’s trance, he knew how muddied it was.

“Well, they said—” She hesitated, young and small, ill-equipped temperamentally to carry the grievances of others around in her possession as their spokesman.

“I’ll talk to them direct,” he said to her humanely. “Frankly, to me it looked like a self-programming eggbeater mounted on triangular wheels.” And what can you destroy, he reflected, with that?

“Oh, they seem to feel it’s a fine weapon,” Miss Bedouin said, her natural, hormone-enriched breasts moving in sychronicity with his notice of them. “I believe they just can’t make out the power source. You know, the erg structure. Before you go to 286—”

“They want me,” he said, “to take a better look at 285. Okay.” It did not bother him. He felt amiably inclined, because this was a pleasant April day and Miss Bedouin (or, if you liked to think about it that way, Miss Bed) was pretty enough to restore any man’s sanguineness. Even a fashion designer—a weapons fashion designer.

Even, he thought, the best and only weapons fashion designer in all Wes-bloc.

To turn up his equal—and even this was in doubt, as far as he was concerned—one would have to approach that other hemisphere, Peep-East. The Sino-Soviet bloc owned or employed or however they handled it—in any case had available to them—services of a medium like himself.

He had often wondered about her. Her name was Miss Topchev, the planet-wide private police agency KACH had informed him. Lilo Topchev. With only one office, and that at Bulganingrad rather than New Moscow.

She sounded reclusive to him, but KACH did not orate on subjective aspects of its scrutiny-targets. Perhaps, he thought, Miss Topchev knitted her weapons sketches … or made them up, while still in the trance-state, in the form of gaily colored ceramic tile. Anyhow something artistic. Whether her client—or more accurately employer—the Peep-East governing body SeRKeb, that grim, uncolored and unadorned holistic academy of cogs,

against which his own hemisphere had for so many decades now pitted every resource within itself, liked it or not.

Because of course a weapons fashion designer had to be catered to. In his own career he had managed to establish that.

After all, he could not be compelled to enter his five-days-a-week trance. And probably neither could Lilo Topchev.

Leaving Miss Bedouin, he entered his own office, removing his outer cape, cap and slippers, and extended these discarded items of street-wear to the handicloset.

Already his medical team, Dr. Todt and nurse Elvira Funt, had sighted him. They rose and approached respectfully, and with them his near-psionically gifted quasi-subordinate, Henry Morris. One never knew—he thought, constructing their reasoning on the basis of their alert, alarmed manner—when a trance might come on. Nurse Funt had her intravenous machinery tagging hummingly behind her and Dr. Todt, a first-class product of the superior West German medical world, stood ready to whip out delicate devices for two distinct purposes: first, that no cardiac arrest during the trance-state occur, no infarcts to the lungs or excessive suppression of the vagus nerve, causing cessation of breathing and hence suffocation, and second—and without this there was no point to it all—that mentation during the trance-state be established in a permanent record, obtainable after the state had ended.

Dr. Todt was, therefore, essential in the business at Mr. Lars, Incorporated. At the Paris office a similar, equally skilled crew awaited on stand-by. Because it often happened that Lars Powderdry got a more powerful emanation at that locus than he did in hectic New York.

And in addition his mistress Maren Faine lived and worked there.

It was a weakness—or, as he preferred supposing, a strength of weapons fashion designers, in contrast to their miserable counterparts in the world of clothing—that they liked women. His predecessor, Wade, had been heterosexual, too—had in fact killed himself over a little coloratura of the Dresden Festival ensemble. Mr. Wade had suffered auricular fibrillation at an ignoble time: while in bed at the girl’s Vienna condominium apartment at two in the morning, long after The Marriage of Figaro had dropped curtain, and Rita Grandi had discarded the silk hose, blouse, etc., for—as the alert homeopape pics had disclosed—nothing.

So, at forty-three years of age, Mr. Wade, the previous weapons fashion designer for Wes-bloc, had left the scene—and left vacant his essential post. But there were others ready to emerge and replace him.

Perhaps that had hurried Mr. Wade. The job itself was taxing—medical science did not precisely know to what degree or how. And there was, Lars Powder-dry reflected, nothing quite so disorienting as knowing that not only are you indispensable but that simultaneously you can be replaced. It was the sort of paradox that no one enjoyed, except of course UN-W Natsec, the governing Board of Wes-bloc, who had contrived to keep a replacement always visible in the wings.

He thought, And they’ve probably got another one waiting right now.

They like me, he thought. They’ve been good to me and I to them: the system functions.

But ultimate authorities, in charge of the lives of billions of pursaps, don’t take risks. They do not cross against the DON’T WALK signs of cog life.

Not that the pursaps would relieve them of their posts … hardly. Removal would descend, from General George McFarlane Nitz, the C. in C. on Natsec’s Board. Nitz could remove anyone. In fact if the necessity (or perhaps merely the opportunity) arose to remove himself—imagine the satisfaction of disarming his own person, stripping himself of the brain-pan i.d. unit that caused him to smell right to the autonomic sentries which guarded Festung Washington!

And frankly, considering the cop-like aura of General Nitz, the Supreme Hatchet-man implications of his—

“Your blood-pressure, Mr. Lars.” Narrow, priest-like, somber Dr. Todt advanced, machinery in tow. “Please, Lars.”

Beyond Dr. Todt and nurse Elvira Funt a slim, bald, pale-as-straw but highly professional-looking young man in peasoup green rose, a folio under his arm. Lars Powderdry at once beckoned to him. Blood-pressure readings could wait. This was the fella from KACH, and he had something with him.

“May we go into your private office, Mr. Lars?” the KACH-man asked.

Leading the way Lars said, “Photos.”

“Yes, sir.” The KACH-man shut the office door carefully after them. “Of her sketches of—” he opened the folio, examined a Xeroxed document— “last Wednesday. Their codex AA-335.” Finding a vacant spot on Lars’ desk he began spreading out the stereo pics. “Plus one blurred shot of a mockup at the Rostok Academy assembly-lab … of—” Again he consulted his poop sheet—“SeRKeb codex AA-330.” He stood aside so that Lars could inspect.

Seating himself Lars lit a Cuesta Rey astoria and did not inspect. He felt his wits become turgid, and the cigar did not help. He did not enjoy snooping doglike over spy-obtained pics of the output of his Peep-East equivalent, Miss Topchev. Let UN-W Natsec do the analysis! He had so much as said this to General Nitz on several occasions, once at a meeting of the total Board, with everyone present sunk within his most dignified and stately presgarms—his prestige capes, miter, boots, gloves … probably spider-silk underwear with ominous slogans and ukases, stitched in multicolored thread.

There, in that solemn environment, with the burden of Atlas on the backs of even the concomodies—those six drafted, involuntary fools—in formal session, Lars had mildly asked that for chrissakes couldn’t they do the analysis of the enemy’s weapons?

No. And without debate. Because (listen closely, Mr. Lars) these are not Peep-East’s weapons. These are his plans for weapons. We will evaluate them when they’ve passed from prototype to autofac production, General Nitz had intoned. But as regards this initial stage … he had eyed Lars meaningfully.

Lighting an old-fashioned—and illegal—cigarette, the pale, bald young KACH-man murmured, “Mr. Lars, we have something more. It may not interest you, but since you seem to be waiting anyhow …”

He dipped deep into the folio.

Lars said, “I’m waiting because I hate this. Not because I want to see any more. God forbid.”

“Umm.” The KACH-man brought forth an additional eight-by-ten glossy and leaned back.

It was a non-stereo pic—taken from a great distance, possibly even from an eye-spy, satellite, then severely processed—of Lilo Topchev.

TWO

“Oh, yes,” Lars said with vast caution. “I asked for that, didn’t I?” Unofficially, of course. As a favor by KACH to him personally, with absolutely nothing in writing—with what the old-timers called “a calculated risk.” “You can’t tell too much from this,” the KACH-man admitted.

“I can’t tell anything.” Lars glared, baffled.

The KACH-man shrugged with professional nonchalance, and said, “We’ll try again. You see, she never goes anywhere or does anything. They don’t let her. It may be just a cover-story, but they say her trance-states tend to come on involuntarily, in a pseudo-epileptoid pattern. Possibly drug-induced, is our guess off the record, of course. They don’t want her to fall down in the middle of the public runnels and be flattened by one of their old surface-vehicles.”

“You mean they don’t want her to bolt to Wes-bloc.”

The KACH-man gestured philosophically.

“Am I right?” Lars asked.

“Afraid not. Miss Topchev is paid a salary equal to that of the prime mover of SeRKeb, Marshal Paponovich. She has a top-floor high-rise view conapt, a maid, butler, Mercedes-Benz hovercar. As long as she cooperates—”

“From this pic,” Lars said, “I can’t even tell how old she is. Let alone what she looked like.”

“Lilo Topchev is twenty-three.”

The office door opened and short, sloppy, unpunctual, on-the-brink-of-being-relieved-of-his-position but essential Henry Morris conjured himself into their frame of reference. “Anything for me?”

Lars said, “Come here.” He indicated the pic of Lilo Topchev.

Swiftly the KACH-man restored the pic to its folio. “Classified, Mr. Lars! 20-20. You know; for your eyes alone.”

Lars said, “Mr. Morris is my eyes.” This was, evidently, one of KACH’s more difficult functionaries. “What is your name?” Lars asked him, and held his pen ready at a notepad.

After a pause the KACH-man relaxed. “An ipse dixit, but—do whatever you wish with the pic, Mr. Lars.” He returned it to the desk, no expression on his sunless, expert face. Henry Morris came around to bend over it, squinting and scowling, his fleshy jowls wobbling as he visibly masticated, as if trying to ingest something of substance from the blurred pic.

The vidcom on Lars’ desk pinged and his secretary Miss Grabhorn said, “Call from the Paris office. Miss Faine herself, I believe.” The most minuscule trace of disapproval in her voice, a tiny coldness.

“Excuse me,” Lars said to the KACH-man. But then, still holding his pen poised, he said, “Let’s have your name anyhow. Just for the record. In the rare case I might want to get in touch with you again.”

The KACH-man, as if revealing something foul, said reluctantly, “I’m Don Packard, Mr. Lars.” He fussed with his hands. The question made him oddly ill-at-ease.

After writing this down, Lars fingered the vidcom to on and the face of his mistress lit, illuminated from within like some fair, dark-haired jack-o-lantern. “Lars!”

“Maren!” His tone was of fondness, not cruelty. Maren Faine always aroused his protective instincts. And yet she annoyed him in the fashion that a loved child might. Maren never knew when to stop.

“Busy?”

“Yeah.”

“Are you flying to Paris this afternoon? We can have dinner together and then, oh my God, there’s this gleckik blue jazz combo—”

“Jazz isn’t blue,” Lars said. “It’s pale green.” He glanced at Henry Morris. “Isn’t jazz a very pale green?” Henry nodded.

Angrily, Maren Faine said. “You make me wish—”

“I’ll call you back,” Lars said to her. “Dear.” He shut down the vidcom. “I’ll look at the weapons sketches now,” he said to the KACH-man. Meanwhile, narrow Dr. Todt and nurse Elvira Funt had entered his office unannounced; reflexively he extended his arm for the first blood-pressure reading of the day, as Don Packard rearranged the sketches and began to point out details which seemed meaningful to the police agency’s own very second-rate privately maintained weapons analysts.

Valis

Valis The Simulacra

The Simulacra In Milton Lumky Territory

In Milton Lumky Territory Lies, Inc.

Lies, Inc. The Man Who Japed

The Man Who Japed Selected Stories of Philip K. Dick

Selected Stories of Philip K. Dick Gather Yourselves Together

Gather Yourselves Together Beyond the Door

Beyond the Door Our Friends From Frolix 8

Our Friends From Frolix 8 Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? The Short Happy Life of the Brown Oxford and Other Classic Stories

The Short Happy Life of the Brown Oxford and Other Classic Stories The Penultimate Truth

The Penultimate Truth Counter-Clock World

Counter-Clock World The Minority Report: 18 Classic Stories

The Minority Report: 18 Classic Stories Now Wait for Last Year

Now Wait for Last Year The Broken Bubble

The Broken Bubble Paycheck

Paycheck Ubik

Ubik Martian Time-Slip

Martian Time-Slip The Shifting Realities of Philip K. Dick

The Shifting Realities of Philip K. Dick The Man Whose Teeth Were All Exactly Alike

The Man Whose Teeth Were All Exactly Alike Mary and the Giant

Mary and the Giant The Man in the High Castle

The Man in the High Castle Puttering About in a Small Land

Puttering About in a Small Land Confessions of a Crap Artist

Confessions of a Crap Artist Mr. Spaceship by Philip K. Dick, Science Fiction, Fantasy, Adventure

Mr. Spaceship by Philip K. Dick, Science Fiction, Fantasy, Adventure Nick and the Glimmung

Nick and the Glimmung Deus Irae

Deus Irae The Minority Report

The Minority Report The Hanging Stranger

The Hanging Stranger The Variable Man

The Variable Man Voices From the Street

Voices From the Street Second Variety and Other Stories

Second Variety and Other Stories A Scanner Darkly

A Scanner Darkly In Pursuit of Valis

In Pursuit of Valis The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

The Transmigration of Timothy Archer The Crack in Space

The Crack in Space The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick 3: Second Variety

The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick 3: Second Variety The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick 4: The Minority Report

The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick 4: The Minority Report The Skull

The Skull Solar Lottery

Solar Lottery Vulcan's Hammer

Vulcan's Hammer The Gun

The Gun The Crystal Crypt

The Crystal Crypt The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick 5: The Eye of the Sibyl

The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick 5: The Eye of the Sibyl Mr. Spaceship

Mr. Spaceship The Zap Gun

The Zap Gun Dr. Bloodmoney

Dr. Bloodmoney Beyond Lies the Wub

Beyond Lies the Wub Galactic Pot-Healer

Galactic Pot-Healer The Divine Invasion

The Divine Invasion Radio Free Albemuth

Radio Free Albemuth A Maze of Death

A Maze of Death The Ganymede Takeover

The Ganymede Takeover The Philip K. Dick Reader

The Philip K. Dick Reader The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick

The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick The Complete Stories of Philip K. Dick Vol. 4:

The Complete Stories of Philip K. Dick Vol. 4: Tony and the Beetles

Tony and the Beetles The Cosmic Puppets

The Cosmic Puppets The Complete Stories of Philip K. Dick Vol. 5: The Eye of the Sibyl and Other Classic Stories

The Complete Stories of Philip K. Dick Vol. 5: The Eye of the Sibyl and Other Classic Stories Clans of the Alphane Moon

Clans of the Alphane Moon Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said

Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said The World Jones Made

The World Jones Made Total Recall

Total Recall Eye in the Sky

Eye in the Sky Second Variety

Second Variety Vintage PKD

Vintage PKD A Handful of Darkness

A Handful of Darkness Complete Stories 3 - Second Variety and Other Stories

Complete Stories 3 - Second Variety and Other Stories The Book of Philip K Dick

The Book of Philip K Dick The Transmigration of Timothy Archer (Valis)

The Transmigration of Timothy Archer (Valis) Autofac

Autofac Dr. Futurity (1960)

Dr. Futurity (1960) Shell Game

Shell Game The Minority Report and Other Classic Stories

The Minority Report and Other Classic Stories Collected Stories 2 - Second Variety and Other Classic Stories

Collected Stories 2 - Second Variety and Other Classic Stories The Third Time Travel

The Third Time Travel The Game-Players Of Titan

The Game-Players Of Titan World of Chance

World of Chance The Shifting Realities of PK Dick

The Shifting Realities of PK Dick Adjustment Team

Adjustment Team The Demon at Agi Bridge and Other Japanese Tales (Translations from the Asian Classics)

The Demon at Agi Bridge and Other Japanese Tales (Translations from the Asian Classics) Collected Stories 3 - The Father-Thing and Other Classic Stories

Collected Stories 3 - The Father-Thing and Other Classic Stories CANTATA-141

CANTATA-141 The Adjustment Team

The Adjustment Team The Collected Stories of Philip K Dick

The Collected Stories of Philip K Dick Electric Dreams

Electric Dreams Collected Stories 1 - The Short Happy Life of the Brown Oxford and Other Classic Stories

Collected Stories 1 - The Short Happy Life of the Brown Oxford and Other Classic Stories Eye in the Sky (1957)

Eye in the Sky (1957) In Milton Lumky Territory (1984)

In Milton Lumky Territory (1984) The VALIS Trilogy

The VALIS Trilogy Paycheck (2003)

Paycheck (2003) The Unteleported Man

The Unteleported Man The Book of Philip K Dick (1973)

The Book of Philip K Dick (1973) Collected Stories 5 - The Eye of the Sibyl and Other Classic Strories

Collected Stories 5 - The Eye of the Sibyl and Other Classic Strories The Eye of the Sibyl and Other Classic Strories

The Eye of the Sibyl and Other Classic Strories The Crack in Space (1966)

The Crack in Space (1966)